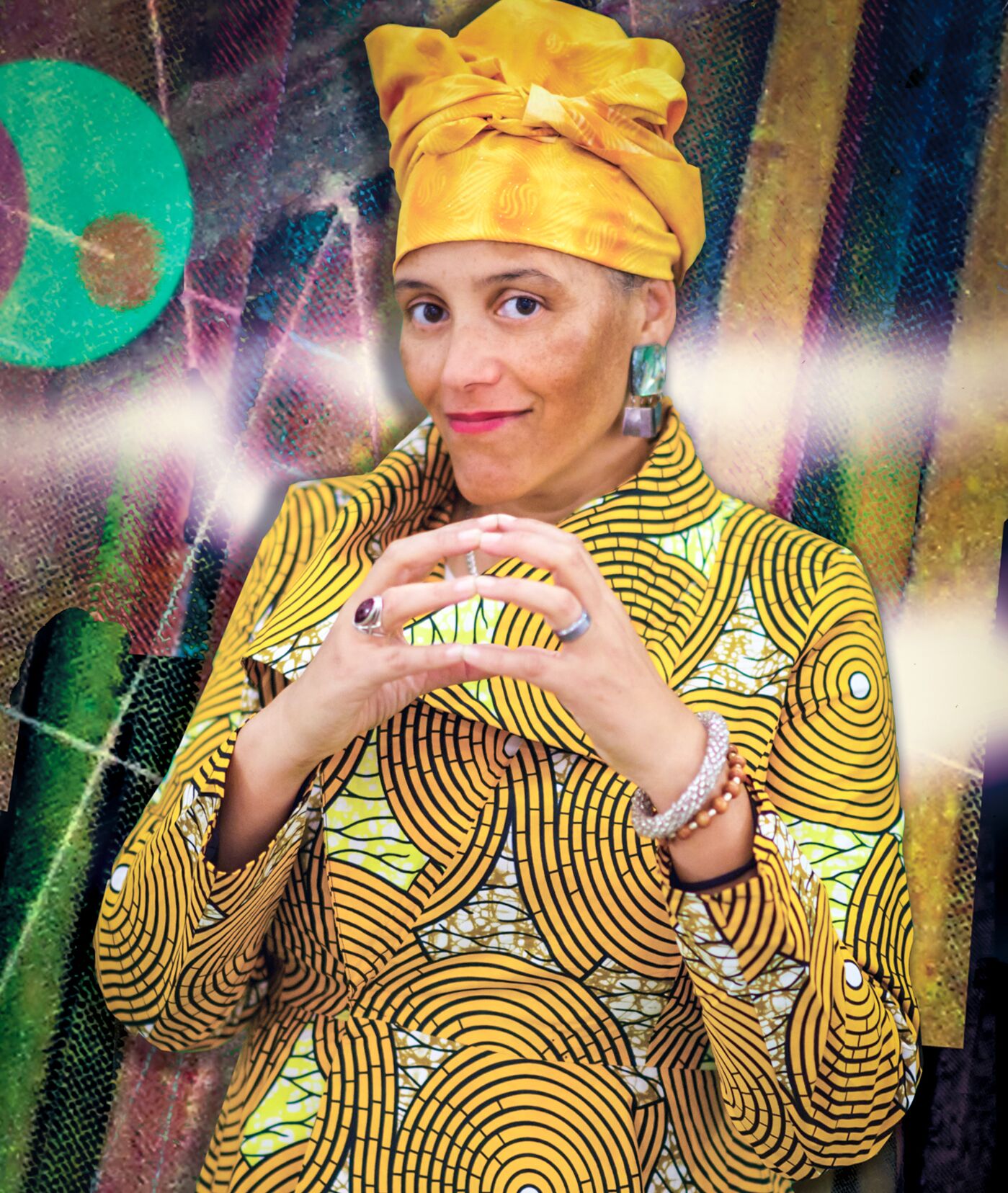

Flutist, composer, and educator Nicole Mitchell is one of the foremost creative musicians of the twenty-first century. Most well-known as the bandleader of the Black Earth Ensemble, she has established herself on the cutting edge through a series of innovative and forward-looking records. Her latest release, Mandorla Awakening II, was released on May 5. In this interview, Nicole discusses her emergence on the Chicago scene, the inspiration of Octavia Butler, and the new record, among other things.

Interview at Astro Diner (6th Avenue, NYC), March 27, 2017

Cisco Bradley: How did you feel that Chicago nurtured you as an aspiring musician back when you were first emerging?

Nicole Mitchell: I think Chicago has been very central to my artistic development for many reasons. Before I moved to Chicago, I didn’t feel a sense of connection with community and I especially didn’t feel a sense of support as an artist. And Chicago really provided a very holistic, nurturing environment. I finally was just a person — not someone who was looked at in some kind of strange way and also it was the first place I found artists with similar vision.

I say this because I’m from Syracuse, New York but halfway through my childhood I moved to Orange County, California, and it was a very racially hostile environment and a cultural desert also on top of that. I left California as a young person and I went to Oberlin for college, where I had some positive experiences, but when I came to Chicago it had a lot of meaning for me personally because my mother was from there.

The times I spent in Chicago growing up were like the best times of my childhood. Because my mother had died when I was a teenager I had a kind of romanticism about connecting to my other family there and to be where she was from so I could connect with some experiences that she had while she was there.

So all of that together with a really vital, vibrant artistic community in Chicago made it very important. My first way of connecting with people was playing in the street. So playing on the street was where I met a lot of the musicians from the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) and I eventually came into that circle where I found a lot of mentorship and also other musicians my age to play with.

Cisco Bradley: Had you been pretty aware of what Chicago had to offer before you got there?

Nicole Mitchell: No. I actually was going there mostly because of the positive experiences I had as a child. Ever since my childhood I felt it was kind of a cultural mecca because it’s such a large Black community that diversity within the community is embraced. So if you don’t have a stereotypical experience in terms of your black experience, it’s no big deal. When you are in,like,a white college or something like that, then there’s all kinds of pressure and other impacts on you and it’s not a normal experience with other black students or with the white students. But in a large black community like Chicago, you can have a more normalized experience which, for some reason, I never could have before that.

Cisco Bradley: You became a member and eventually president of AACM. Were there specific people in that organization that mentored you or had a deep impact?

Nicole Mitchell: Definitely. I would start with Maia, who is someone that is not as well-known but who is an amazing composer and multi-instrumentalist who came out of what I would call the Phil Cohran school. She was one of the first musicians I met and we bonded immediately, playing together and developing ideas and concepts for starting a group.

So SAMANA was an all-woman ensemble and it started out as myself, Maia and Shanta Nurullah. Shanta and myself were brought into the AACM by Maia. And so that’s how actually I came into the membership. SAMANA became the first all women ensemble in the AACM. I arrived in Chicago in 1990, SAMANA began in ‘92 and I became a member of AACM in ’95.

Also, Ed Wilkerson was a really amazing mentor. He’s one of my favorite composers and he’s still out there in Chicago improvising and performing. If you look at his 8 Bold Souls projects you’ll see he really is within the lineage of Duke Ellington.

Ernest Dawkins is the current president of AACM. I spent some time playing in his large ensemble, the Live The Spirit band, in the late ‘90s. I also came up with other members like David Boykin, who I’ve worked with a lot together. We’re like peers, but I learned a lot playing his music. He became a member shortly after I did.

And then George Lewis, Anthony Braxton, Wadada Leo Smith have really been a big impact in addition to Roscoe Mitchell and Arveeayl Ra. Hamid Drake was like a big brother and he opened a lot of doors for me and we started Indigo Trio. The strongest thing about the membership is this idea of supporting each other in your original ideas even if you don’t agree on what those ideas are. So you have such a diversity of aesthetics and concepts but everyone, you know, supports each other. So I think that’s what makes it rare.

Cisco Bradley: I wanted to talk to you about your Black Earth Ensemble particularly because it’s been your longest running project and you’ve accomplished so much with that. You describe it as a celebration of the African American cultural legacy. The music embraces the ancient past and paints vision of a positive future and that the music is the weaving of swing, blues, avant garde jazz, bebop, African rhythms, Eastern modes and Western classical sounds – an incredible list of things. I wonder if we could unpack that a bit and talk about the cultural legacy that you feel like you’re contributing to; Afro-futurism and the continuum of past, present, and future.

Nicole Mitchell: Black Earth Ensemble, I can’t believe 2018 will be our 20th anniversary! So I’m really excited about that. It was my first group that I put together and has been the longest standing.

I wanted it to be flexible, because no matter what the project was I wanted to be able to change instrumentation. So the group changes in size and instrumentation depending on the project.

But what’s also important, is that there’s not that many “jazz” groups where you have not only a woman bandleader but you have a gender balance within the group and you also have a multi-generational membership of the group. I like working with other badass women musicians in BEE like Renee Baker, Tomeka Reid, Jovia Armstrong, Ugochi, Mankwe Ndosi and others. That’s important to me.

And, also, I see BEE as making a contribution to contemporary African American culture, in terms of art. A long time ago, I worked at Third World Press. I spent 13 years working there. It’s the oldest African American book publishing company in the country, and I spent time reading manuscripts when they were coming in and I discovered that there are really three kinds of Black art in terms of how people approach it.

One is reflective where they focus on helping us to remember very important things because our history is constantly being re-written by someone else or ignored. So if you’re not assertive in retelling a history that’s not considered mainstream, it’s not going to be remembered.

Then I would say the majority of black artists are focused on the present in kind of showing us what we’re looking at and giving us a big picture of how things are and maybe what needs to be changed — a kind of social commentary.

And then the last group of artists, which is the smallest group, are visionary and they try to give us more of a vision of what things can be so that we can move forward into it. And I would say there are starting to be more artists in this category now more than ever, though if you look back, it’s always been the smallest group of people. And that’s the group that I’ve been aiming to contribute to in terms of my sense of identity as an artist. So that means, in a way, kind of putting those three things together, which I think the Art Ensemble of Chicago and Sun Ra define really well: the concept of ancient to future.

And now we have this really huge focus on this concept of Afro-futurism that’s happening in the last five or ten years, even though there have been artists with those ideas for decades more, you know, but now it has a name and people are focusing on it.

Cisco Bradley: It’s such a commanding list of influences you are weaving together. Can you talk about your creative process?

Nicole Mitchell: Some people have a very linear approach or an anecdotal way of doing their music. I prefer to embrace a lot of things. I call it a spherical approach, to reach from all different sides rather than one single direction that I’m going.

But then there’s always the risk of people saying, “Well, then do you have direction? Do you have a style? Do you have an approach? Or do you just kind of go all over the place?” So I can be guilty of people seeing what I’m doing that way.

Cisco Bradley: What’s your response to that?

Nicole Mitchell: I would say music is supposed to be fun so why would I limit myself? Endless possibilities is my mantra for creativity. The idea is that you can create something familiar and bridge that with the unknown. Why limit yourself?

Cisco Bradley: You talk about presenting a positive, healthy and culturally aware image of African Americans. How have you been doing that?

Nicole Mitchell: I deal with some dystopic themes sometimes, in terms of Xenogenesis, for example, but there is always a sense of self-determination and resilience that’s always expressed in my music. That’s the best way that I exemplify that.

Also, there is still a lot of segregation in music. If you look at me as an artist, you could see that I’m aware of the impact of cultural collaboration. You see that I work with a lot of different people, different projects, but it’s important to me to always challenge myself and to be inspired by new experiences, which means working with different people all the time. You’re not going to look at me as an artist and then see oh, she only plays with white people or oh, she only plays with Black people, you’re going to see me working with a lot of different people.

But it’s still important to me that I’m going to cover material that speaks directly to the Black community but still has meaning for anyone else that experiences it. And, I’m going to do that through working with the musicians I work with and through the projects that I choose to focus on. I see that as being holistic, dealing with well-being for myself and expressing well-being to everyone else. A lot of people who think they are conscious and progressive have a lot of blind spots in terms of that.

Cisco Bradley: I know what you mean. I witness this all the time. I’m amazed at how primitive the discussions are sometimes that I have with people about issues of representation. Just basic.

Nicole Mitchell: And how is it that someone can consider themselves supportive of egalitarianism and all this stuff but then they don’t ever work with artists of color or women? I don’t really get that.

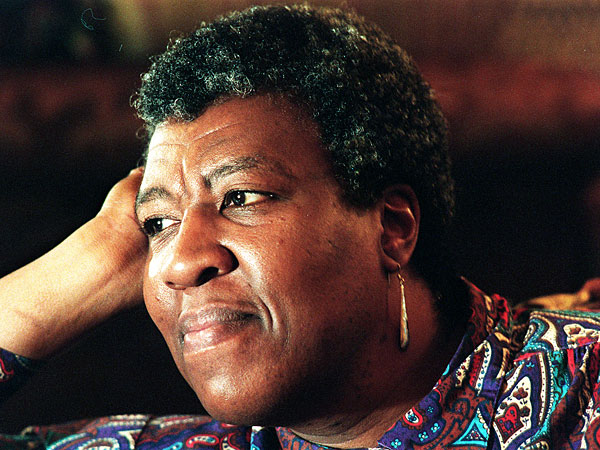

Cisco Bradley: You have engaged directly with science fiction writer Octavia Butler. When did you first come across Octavia’s work?

Nicole Mitchell: When I was a teenager. I grew up in an unusual household. My parents were part of a very small community of African American’s who were into new age thinking. They were into meditation and yoga. My Dad was a big sci-fi Trekkie fan and talked about UFOs all the time. My Mom was a self-taught artist but she would be making paintings of multiple suns setting across the landscape as if it was from another planet … or Black women holding their children sitting on Jupiter or something like that. And then the Octavia Butler books were right there on the shelf so I discovered them pretty early.

And then I had the chance to meet her in 2006 at the Black Writers Conference at Chicago State University.

Cisco Bradley: Just before she passed?

Nicole Mitchell: It was. Because I met her and then I decided I wanted to do a project on her and so I actually applied for the Chamber Music America jazz commissioning project.

Literally, the day I put the proposal in the mail was the day she died. I put it in and then I found out like the next day that she died that day, so I committed to definitely do the project. But it’s amazing now how her work is becoming more and more important to people, which I think is great.

Mandorla Awakening II, released on May 5, is coming from my own sci-fi narrative.

Cisco Bradley: So what are the ideas and narratives you are working with in Mandorla Awakening II?

Nicole Mitchell: I ask a question, which will take me probably a long time to answer, “What would a technologically advanced society look like that is in tune with nature?”

Growing up as a kid you see movies and read stories and it’s always a dichotomy, good vs. evil, but at some point you realize that truth is not necessarily cut and dry in that way. So Mandorla Awakening II is really about colliding these contrasts. Like looking at what are the overlapping positives between two so-called disparate things.

For example, you have the urban and you have the country, you have earth-based culture that has been going on for thousands of years and systems that are more aligned with nature, not destructive of the environment and earth. And then we have so-called technology in all this but have we really made progress if people aren’t treating each other any better that they were thousands of years ago? Is it really an illusion that we have progress? And what would real progress look like?

Cisco Bradley: It sounds like a deep record. That’s amazing.

Nicole Mitchell: I’m hoping this music helps people or inspires people. For example, to ask architects what is green architecture or green technology? How can we actually develop better human interaction where people’s needs are being met but we’re actually treating each other on the big picture more humanely?

If we view human beings as one organism then we’re really just suicidal. When you see war and you see people, even one group killing the other either out of greed, which is mostly the case, you know, something that one group has that the other one wants, or religion, which is easily a rationalization, it’s really just like “humanicide”. It’s really like the human race killing itself. So why are we like that and how do we stop being like that? So that’s what it’s addressing.

I want it to have dialogues between different musical languages in this idea of coexistence vs assimilation. So I have Kojiro Umezaki on shakuhachi. I have Tatsu Aoki on taiko, bass, and shamisen. But then you have Avery Young singing, coming from a gospel background and then you have other musicians, some with classical influence, some with blues influence and how do you coexist with all these ideas?

I try to under-compose rather than over-compose and use graphic scores and a mixture of notated graphic scores so that people have enough space to be themselves, to be authentically who they are but also to get the ideas across that I want to share. So, it is a big experiment. But I think I’ll probably do a lot more with the idea, so it’s kind of the beginning.

Cisco Bradley: The beginning of a multi-record project?

Nicole Mitchell: I think so. This is really the second one. The first one was a work in progress which is not released but I’ll probably release it later. Because it’s a completely different storyline that it was based on and it had choreography and video. This one also came with video by Ulysses Jenkins. I’m just releasing the music, but when I perform them live, I use a video as well.

Cisco Bradley: What do you communicate with the videos?

Nicole Mitchell: I’ve become fascinated with video and this is my first work in terms of my vision of what I want to do with it. So, it’s a little bit rough but I’m having a lot of fun with it. Ulysses Jenkins created most of the images and I worked as the film director and also edited everything the way I wanted it so…

Cisco Bradley: Do you ever use movement or dancers or anything like that?

Nicole Mitchell: Yeah. The first Mandorla Awakening had dance, though it wasn’t documented well. It was just one performance.

Cisco Bradley: I only ask because William Parker once said to me that when he heard Cecil Taylor’s music, he saw dancers in his mind. I must say I had the same feeling when I first heard your music. I just felt like there was so much movement in it.

I was going to ask what is the latest you have been doing with Black Earth Ensemble?

Nicole Mitchell: I premiered a commission on April 8 in Chicago. It’s a tribute for Gwendolyn Brooks, another poet. It’s her centennial. There are a lot of events in Chicago celebrating her because she was poet laureate of Illinois and so we premiered a new piece featuring her poems in spoken word.

And I have another project with another poet who just turned 75, Haki Madhubuti, the founder of Third World Press. Third World Press is going to have its 50th anniversary so this will be in their book catalog. Liberation Narratives will bring his poetry to another audience, through music with the Black Earth Ensemble.

Cisco Bradley: Has that already been debuted?

Nicole Mitchell: Yes, in Chicago. It will probably be released in September 2017.

Cisco Bradley: How do you integrate your work with poetry? Does it take a certain kind of creative process?

Nicole Mitchell: Well, I think I’ve been a poet longer than I’ve been a musician. I’m really excited that I have a new piece that I wrote for the new volume of Arcana that’s coming out. I feel like this is kind of a new chapter for me as an artist, to start pushing my own writing out more. Incorporating poetry has been very natural to me, even if it’s other people’s poetry.

I think that my music — a lot of times when I’m composing — it starts with narrative, which is maybe why you see dance because there is usually a story behind the song even if it’s not stated or given to the audience. So I’ve embraced this even though I know that for a lot of people this is a very old and outdated in terms of as a way of making music, but I still like it.

Cisco Bradley: You said you’ve been a poet longer than you’ve been a musician. Have you been writing poetry through the years?

Nicole Mitchell: I’ve been writing since I was like 11, I think, but I’ve never really published anything.

I mean, if you look at Anthony Braxton’s box set from Iridium, I have a poem in there I think in the liner notes. And I have something that was published in the Giving Birth To Sound: Women In Creative Music that came out last year on Buddy’s Knife.

And, other than that, I don’t think there’s anything out there. I mean I have a 300-page book that I’ve never released.

Cisco Bradley: So when is that going to happen?

Nicole Mitchell: I don’t know. I guess when I feel more comfortable about it. I think I’m really self-critical because I didn’t really train to be a writer even though I’ve been writing and, also, I have kind of a rebellion against getting a writing degree.

Cisco Bradley: As a musician, what was your process for training or learning?

Nicole Mitchell: Well, I actually studied classical flute. You know, I was focused on that first.

Cisco Bradley: And you did that at Oberlin?

Nicole Mitchell: I started at UC San Diego and then I went to Oberlin, then I finished in Chicago. The focus was classical. I didn’t really study jazz, I suppose. I was a jazz major at Oberlin. But, that’s why I left Oberlin because I was the only woman in the whole jazz program. It was the first year of the program and they didn’t know what to do with me. And I constantly told by my teacher, “You’ll never make it anywhere playing jazz flute.” They told me that every week, so I wondered why am I spending all this money doing this? So I left.

Cisco Bradley: Good for you.

Nicole Mitchell: So I would say my training was not linear? I guess nothing with me is linear. But, I’ve had some good teachers. I studied composition with John Eaton when he was teaching at University in Chicago. He was a microtonal opera composer who also happened to have a chapter in his life where he performed with Eric Dolphy a lot in Europe. So we clicked really well.

I was a scholar in residence at University of Chicago. I wasn’t a regular student at University in Chicago, but I was allowed to take some classes. So I studied with Eaton and I also played in the orchestra and won the Concerto Competition while I was there. I played the Mozart concerto with the orchestra. I spent five years playing piccolo with the Joffrey Ballet Orchestra and the Chicago Sinfonietta in Chicago before I moved to California.

And I also like studied with James Newton. He had an impact on me as an improviser — direct artistic lineage right there.

Cisco Bradley: Can you be more specific about what you learned studying with James Newton?

Nicole Mitchell: A lot of it was intuitive but when we were working he would always make time for us to improvise together. And I think that oral tradition is important, working with someone who is a master. I think that still is a really important aspect of jazz music even though people put more emphasis on going to college because they have a degree, but there is still an oral tradition.

And I was very influenced also by Fred Anderson at the Velvet Lounge in Chicago. Even though I never took a lesson with him, I listened to him rehearse and practice. He talked a lot about the music. He’d come in the afternoon, you’d sit there, and he would play recordings for you and break them down and talk about Charlie Parker and his soloing — stuff like that. So there was a lot of stuff that was happening in the margins.

Cisco Bradley: So maybe we could talk about Sonic Projections. One of those was a tribute to Fred.

Nicole Mitchell: Thanks for bringing that up. I think it’s like a sleeper, right?

Cisco Bradley: Yeah! I’m curious about your concept for that group and for those specific musicians: Craig Taborn, Chad Taylor, and David Boykin, and I would like to hear you talk about your tribute to Fred.

Nicole Mitchell: I really believe in that group and I really believe in the music, but that group did not tour at all. The only performances was Vision Festival for the The Secret Escapades of Velvet Anderson and the Chicago Jazz Fest for Emerald Hills. And that’s basically it. So each record literally had one performance. I’m not really sure why that is, because I think it’s some of my strongest music.

Cisco Bradley: I agree.

Nicole Mitchell: And then the musicians are absolutely amazing. So I’m not sure what happened with that.

I really love that group because it’s kind of like a New York-Chicago overlap, you know because Chad had his history in Chicago and Craig actually has a history from the Midwest. At the time, Craig and Chad were in New York, David and I were in Chicago and it was really exciting. It was just a really exciting chemistry.

I wanted to face the challenge of not having a bass player, I was really excited about writing without one. So it really exposed Craig’s amazing playing in some wonderful ways. I had a really great time writing for that group. Whereas I under-compose from Mandorla Awakening, I kind of over-composed for them in a lot of ways because I knew they could do it. Whatever I wrote, no matter how hard, they could do it.

Cisco Bradley: I wish we had more time to talk. Let’s keep in touch and do another interview in the future. Thank you!

1 comment

Join the conversationInterview with Nicole Mitchell – Avant Music News - May 9, 2017

[…] Jazz Right Now. Ms. Mitchell is getting busy in support of her latest […]

Comments are closed.