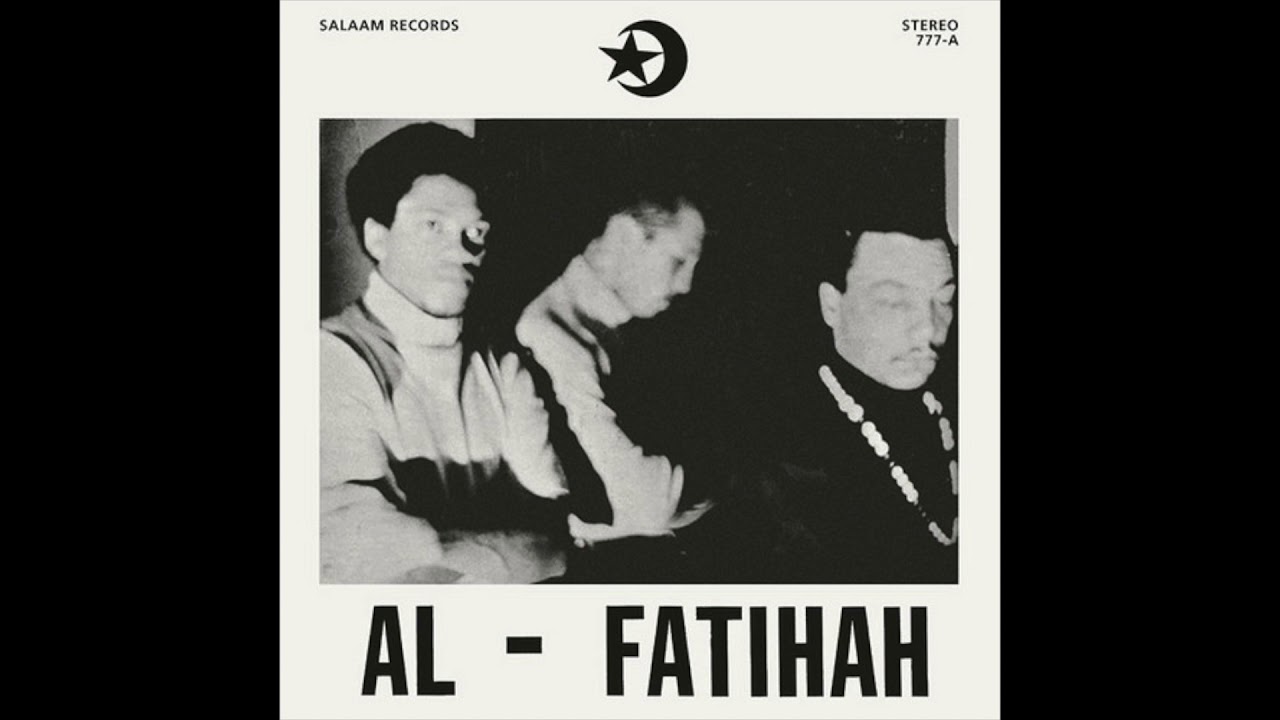

In the late 1960s, the Black Unity Trio exploded onto the free jazz scene comprised of saxophonist Yusuf Mumin, cellist Abdul Wadud, and drummer Hasan Shahid. Based primarily in Cleveland, the band toured in various parts of the United States, especially on college campuses with active Black student organizations. The band exemplified some of the highest reaches of free jazz of the period, full of energy, expression, and vision. Black Unity Trio recorded their only release, Al-Fatihah, which they released in 1969. Shortly thereafter, the band broke up. Because the record was originally sold in a run of only 500 copies and was self-released on their own self-run label, Salaam Records, it has been difficult to find for many years. Recently, a used copy sold for over $6000 online. In 2019, the members of Black Unity Trio were approached about reissuing Al-Fatihah. The music was, in many ways, a tribute to John Coltrane, who had passed away about a year and a half before this recording. “Many people seemed to stop in their tracks when he passed,” drummer Hasan Shahid remarked, “but we wanted to keep it going and go even farther.” The opening track is streamable below:

The record may be pre-ordered prior to being released on November 27.

In the following interview, I talked to Mr. Shahid, the band’s drummer, and we discussed questions that I formulated with input from writer Gabriel Vanlandingham-Dunn. Because Mr. Shahid was interviewed by Pierre Crepon in The Wire in March, we aimed to avoid repetition, and instead build from that perceptive interview going in new directions.

Cisco Bradley: I understand that you are originally from Birmingham, Alabama, and that your father was also a jazz player. What did you take from that experience?

Hasan Shahid: My father, Amos Gordon, Sr., was a master of the music. I didn’t get all of his DNA, but I did learn a lot. He grew up without a father, his mother was not a high school graduate, and they had no money. They came out of a mining camp town in Alabama. She bought him his first clarinet for $7, paying 25 cents a month on it for a while. He wanted to play saxophone, but the school band needed a clarinetist, so he did that first. He was a perfect A student all the way through from elementary school through high school, growing up in Alabama in the 1920s. He could play any instrument. He had perfect pitch. Later when he played with a big band, he could tune up a whole orchestra by ear and he always knew which instruments were out of tune. Later he went to Tuskegee Institute [today Tuskegee University] on a music scholarship, where he played with Booker T. Washington’s granddaughter who was a pianist. But because the administrators did not like him playing with someone they considered “royalty” and he was considered to be from the wrong side of the tracks, he was asked to leave. He then transferred to Alabama State College so that he could play with Erskine Hawkins. They went around the country playing dance music at Black colleges at the time playing hits such as “Tuxedo Junction.” While on tour in the South, Louis Armstrong called Erskine asking him if he knew any alto players who would be able to play his book of music. So daddy took that book and played it upside down, backwards, and sideways! Louis hired him and took him to New York. My father was in the movies, New Orleans with Armstrong and Billie Holliday, and in Boarding House Blues with Moms Mabley and the Lucky Millinder Band. When Charlie Parker came to town and needed a gig with Louis, he played third saxophone because he was an average sight reader, my father played first. When we lived on 186th and St. Nicholas in New York, Billie Holliday lived upstairs from us with a trumpet player from Alabama named Joe Guy. My daddy was friends with Sonny Blount, who later became Sun Ra. My father played with lots of other musicians. He played first chair saxophone with Louis Armstrong, Lucky Millinder, Andy Kirk, and Erskine Hawkins. His last tour was with Bull Moose Jackson. At that time, I would only see my daddy about once a year because he was touring all of the time, though we moved around in New York and lived in Chicago for a little while, which was the jumping off point for touring. We stayed in New York in the winter and Chicago in the summer, when he would travel to the west coast because the busses could get through the Rocky Mountains. He played the east coast, the midwest, the southeast. It got to the point that I forgot what my father looked like and one day when I was five years of age he came back home and rang the doorbell and I yelled because I didn’t recognize him. Because his father had walked out on him and his mother, with me not recognizing him, that was it, he quit the music. He gave all of that up to be with his son. Then we came back to Birmingham.

CB: Did you grow up with any music from your grandparents? I’m curious if there was any gospel in your family or any spirituals that were passed down through the family.

HS: My father’s the basic beginning of the music, which goes back to 1926, 1928. That’s almost 100 years right there. Before that, my basic family is filled with teachers. Majority of my family were teachers and other professions. I was just saying my grandmother’s brother, my uncle Willis, was the first college graduate, from Tuskegee around 1904. He was the first black dentist in Decatur, Alabama and Montgomery, Alabama. I mean there are a lot of instances of that type of professional, but none of them were musicians of any sort. My father was the beginning of it all. Believe me, he left a history that is documented that will fill up three quarters of those hundred years. That’s what I’ve been around all my life.

As I sat there and absorbed it, took me on a gig at 12 years of age with Laura Washington who had cut the song, “I’ve Got the Right to Cry” with the Erskine Hawkins Band. I’ve been playing since then. That’s all I know how to do. That’s all I ever wanted to do. I didn’t want to teach. I wanted to be a performing musician, that’s where I get the biggest thing out of it. Didn’t necessarily want to write. Couldn’t write because I didn’t pay attention to that part of it. I just enjoyed playing and it was mostly spontaneously created. We’d just go there and they’d count the tune off and there were no charts to read, anything like that. A reporter came into the studio in Chicago, and asked Pops, “Hey, Louie, you read music?” Pops’d say, “Yeah, as long as it doesn’t get in the way.”

CB: What was you and your family’s involvement in the rising Black political consciousness in Alabama in the 1950s and into the ‘60s?

HS: My family were artists and educators. They had music studios for youth and led youth bands. My mother trained the majority of the students who had graduated from the state colleges that were coming to teach in Birmingham. We were not really involved in the political arena. My mother being from Montgomery and her family’s home church is Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, she knew Martin Luther King and was friends with Rosa Parks. Rosa Parks attended my Aunt Stella’s funeral when she died in Detroit. Montgomery is such a very small town that everybody knows each other. She was personal friends with both of these people, Martin Luther King at Dexter Avenue as well as my family, including her mother, were there. My uncle Willis, his son, all of my family all attended the Montgomery Church. All of them were funeralized there.

After she retired, my mother became political by being elected as the neighborhood president. She was the neighborhood president of Pratt City, Alabama, for about six or eight years. I have some pictures of her to send to my kids, where she’s meeting and shaking hands with Nancy Reagan. She had a lot of involvement with the first Black mayor, Richard Arrington of Birmingham. Everybody knows my people because they were well-known and very good teachers and had a hell of a outstanding reputation for the music and the academic students that they turned out. My mother went back to Alabama State and got her master’s in education. My father went to NYU on the G.I. Bill in 1950 or 1951 and got his master’s in history.

CB: So you arrived in Cleveland in the late sixties?

HS: I arrived in Cleveland then and that brought together the Black Unity Trio. April, early May of 1968, a vocalist, Countess Felder that I had performed with in Birmingham, found me in New York. Had a three month contract for one of the big hotels in downtown Cleveland on the lake. She asked me if I would accompany her. I hadn’t even brought a set of drums with me because I was coming up there to go to grad school and please my mother. I was accepted at the New School of Social Research. I was going there to study abnormal psych. I was a psych major, sociology major combined; two minors, two majors. I went through a lecturer that had about 200-300 people in his class. I happened to be the only person of African descent that I could see. The instructor was German, so I couldn’t understand what he was saying. After a while, it just finally dawned on me that this isn’t about me. What am I doing? And I withdrew. I didn’t have any drums, so when Countess offered me a gig, she and her husband were together. They had a nice house there. They not only gave me a place to stay and fed me, Countess went out and bought me a set of drums. It’s a set of drums that you hear on the album, Al-Fatihah. I got hooked up with a couple of people that she knew including an organ player

We had a gig in Columbus, Ohio for about two weeks. They put us up in a motel. That’s where I met Nancy Wilson, before she became famous. She was singing at a club in Columbus, Ohio called Room 222 or something like that. I’ve forgotten. Nice person. Just realized within the last two years, talking about Alabama home, who Nancy sounds like. I found that out by listening at somebody that I thought was Nancy singing. At the end of the tune, they announced that Nancy is a reincarnation of a woman from Tuscaloosa, Alabama, by the name of Dinah Washington. Just listen at her. Sounds just like her. Phrases just like her. So Countess lived in East Cleveland, off of 127th Street. She was out walking to go to the grocery store and walked by this record shop that was called Cosmic Music.

She peeped in there, and the full collection that was on the wall, was all new music. In fact, it was an entire collection of ESP albums at that time. She knew about Sun Ra’s albums up there, that’s Birmingham. She’s in Cleveland, so she knew something about Albert, so goes in to check it out. Starts talking to Yusuf Mumin. In the conversation, Yusuf tells her that he has a cello player and they’d been trying to do some things as a group, but they looking for a drummer. She said, “Wait, I got a friend of mine that I just brought here from New York that is crazy about Trane,” because we were all Trane fanatics. She said, “Hold on, I’ll go get him.” They brought me back up there. We went in the back. I never will forget it. Abdul Wadud was back there fumbling around, and nobody gave no directions or nothing. We just start. Played for about 30 minutes. Fierce, blistering.

After we got through, Yusuf looked at Abdul Wadud and said, “Well, man, what you think?” Abdul said, “Hell yeah, man!” Like you’ve heard the statement love at first sight, it was love at first hear. We knew that this was the Creator giving, that was much greater than we were. We respected it and cherished it that much. That’s why I don’t know of any other album in the jazz of the cosmic music medium that opens with an opening prayer. Listen at that prayer. It’s the prayer of Abraham/Ibrahim. It says, I’ve turned myself upright. I’m not amongst polytheists. My prayers, my sacrifices, my life and my death, are all for the Creator, Lord of the worlds. Then it blows, it explodes. People used to say, you all start out, where you going? Trane was a Libra. Two sides, two expressions. All the way up to the album, Cosmic Music, Trane would always start off with one side of the Libra, a beautiful childlike melody. Then he’d build it up and explode.

When he got to the Cosmic Music album, one tune on the album was called “Manifestations” and it started just like we did, with an explosion instead of the little childhood melody. That’s what we experimented with and we could take it anywhere. When we did gigs, never played in a nightclub. I’m proud of that. Miles said once, when you go to see Itzhak Perlman, it’s so quiet you can hear a pin drop. So why when you come see me, and disrespect me when I’m trying to create this art form for you, that you’re howling, talking across the room, clinking glasses, serving drinks, changing money, and say, you want to question me about why I turned my back to you? It’s because you turn your back on me.

Have you ever been to a symphony and seen someone clap after every instrumental solo? Why in the hell are you going to break my concentration? You just being phony. I get emotional about that. That’s what the music is about. That’s what it’s for. It has to be used positively or else the Creator, as he has done, I bear witness, took the music away from me.

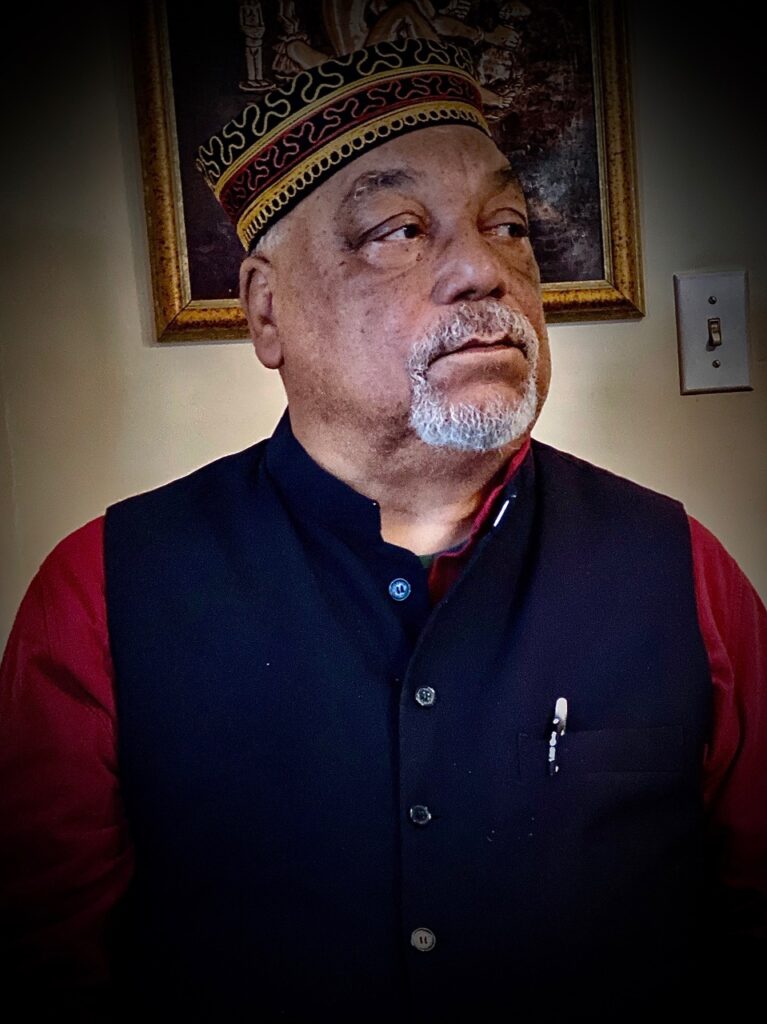

Hasan Shahid

CB: When you met in Cleveland in 1968, had you all already converted to Islam?

HS: Abdul Wadud and I did. Most of the musicians that came out of Cleveland, dealing with the new music how strange it might be, were probing Islam in some form or fashion. The Nation of Islam was very strong in Cleveland. When I came in and stayed with the bass player that we lived together, there was the Imam Mutawaf Shaheed (Clyde Shy) who was the bass player with Albert Ayler, his first bass player. They were all Sunni Muslims, which was very different than the Nation of Islam. Yusuf took me to a meeting with the Nation and I was shocked. I looked at it and it just wasn’t my cup of tea. I was looking for something more, that’s why I kept searching. I even went as far as writing my letter and sending it to Elijah Muhammad to get my X and later we sent him a copy of Al-Fatihah.

The Black Unity Trio broke up when the feds took me out of the mosque in chains, January 13, 1970. Brought me back to Alabama for trial that September. Got three years’ probation because I had the exact same case that Muhammed Ali had just won in the Supreme Court. That’s what the judge said. Didn’t make no sense to send this case any further because it had already been proved. What they did, they accused me of being crazy. Before they went any further, went to trial, I had to go to a psychiatrist to be examined for my sanity and my religious sincerity. And show how your life becomes the acceptance on blind faith and things that the Creator says in the Quran that happened and are going to happen, actually start happening, and you can see the blessings. The German psychologist that they sent me to, and my lawyer said, “If you don’t go, they can incarcerate you until you do. That’s the law.” The psychologist happened to be a German who had lived in India for a number of years around some Muslims, so he knew the religion. We could communicate, not in German or English, but the little bit of Arabic that I knew and a little bit that he knew. He asked me questions like the Fatihah, and the Shahada, prayers, name of the prayer. I knew all of that.

So by the time I was in Cleveland, I’d already been exposed because I was very good friends with the minister, James Shabazz (James London) of the Nation of Islam here in Birmingham. In fact, we were avid chess players. My first year at Howard was the fall of 1961, September entering in DC. In October of 1961, as a low country bumpkin, I happened to be sitting on the front row at a debate. The debate was between Malcolm X and Bertrand Russell. I had never in my life, even with my father, heard somebody hook up history with current events, the way Malcolm did. He fascinated me. The first time I went to New York by myself to work was the summer of ‘62. Where was I every Saturday? At the theater where Malcolm spoke at 12 noon in Harlem, the Audubon, where they killed him.

I was fascinated by the Nation of Islam to a certain extent, but it was just something about it. I was going through the nationalist or Afrocentric, African clothes, hairdos and stuff. The bald head, bow ties, sharkskin suits and the Cadillacs just wasn’t my cup of tea. I was looking for something more spiritual. Here’s how the Creator directed me. We played a lot of gigs at Oberlin because the last years or so, that’s where Abdul Wadud was attending school, so we played down there quite a lot. We were looking for a bass player. We had heard that Mutawaf Shaheed was the bass player that had played with Albert Ayler. A fantastic bass player. Strong. Made windows shatter. When he got done playing, his hands would be smoking. Anyway, he was at the mosque, same mosque that the feds took me out of in chains on Superior. When we walked in the door, a brother named Mubarak from Detroit was calling the sunset prayer athan. It just penetrated my heart. As a child, every Sunday, my grandmother would shout every Sunday and it was embarrassing, and I didn’t understand it. When I heard athan and the same thing about playing the music, I knew then for the first time in my life, what my grandmother shouted about, because I knew this was what I was looking for. I became Muslim. A brother from Philadelphia, who’s deceased now, Hasan, gave me Shahada that night in that mosque. I moved in the next day studying for nine months.

CB: Did the Ahmadiyya have a big presence in Cleveland?

HS: Yeah, Ahmadiyya was all through the Midwest and they were heavy. A lot of musicians out of Philadelphia were Ahmadiyya. Our first exposure at that time, the Tablighi Jamaat was heavy. That’s why the first exposure of most of the people that came out of the latter ‘60s, were Tablighi Jamaat that was coming out of Pakistan.

CB: When did you study at Howard University?

HS: You familiar with Nkrumah Toure? Stokely Carmichael?

CB: Of course, yes.

HS: That’s what he changed his name to when he married Miriam Makeba, the singer. Stokely and I lived in a dorm together and became close friends when they were forming Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee at Howard in 1962. I left Howard in the spring of ‘64 to work on voter registration in Sumter, Lowndes, Macon, and Jefferson counties in Alabama. I stayed and I enrolled in a local college there called Miles College, which I graduated from in January of ’68 and got the acceptance to the New School of Social Research in New York.

CB: So you were going to go to the New School for a masters?

HS: Yeah, in abnormal psychology and that was to please my mother, bless her soul. That’s when I saw, like said, I was the only Black person in the class trying to listen to a German tell me about Sigmund Freud and Edgar Allen Poe, a philosopher and a psycho. I said to myself, ‘I don’t think that’s about me professor.’ I withdrew because all I wanted to do was play. I also wanted to please my mother who I loved dearly. That’s where I really hung on and finished college at Miles. It was for her, for all the things that they’d done for me, only child. They did everything. Parents, fantastic people. That’s how I get back to Alabama with Stokely in 1964 and played for two years with a then up-and-coming vocalist Nell Carter. That’s where I’ve met Jesse Taylor, the tenor player who I met Trane together with in the summer of ’66. He had just got out of the service and he was a music major at Tennessee State. Awesome tenor player.

Jesse is who really took me into Trane musically and explained things to me, which enhanced my comprehension and how to do things better rhythmically. I used to have two albums in 1961 and a little small, one-speaker turntable, record player. I had Trane’s My Favorite Things and this album by Cannonball called Spontaneous Combustion. When I first heard My Favorite Things with Elvin Jones playing his 6/8 eight rhythms, I knew automatically it was something different. In a conversation with Ron Carter, he says, so beautifully, that it was before Elvin and it was after Elvin. It was before Kenny Clark, before Papa Jo Jones. It was after Papa Jo Jones, after Kenny Clark. Do you know what they call it? New York style or drumming. I played with some cats down here, kids that I grew up with like Jothan Callins who cut the album Winds of Change with Joseph Bonner, Cecil McBee, and Norman Connors. My father’s students were very successful in New York, and the first thing they tell me, when we play, you don’t play like a New York drummer. I don’t want to play like a New York drummer.

When I got to New York and started playing with some of these people who were basically music majors, they said, you’re a free drummer. I never liked to play bebop. The expressions are too short. I like long expressive things and that’s what fits my personality. That’s something that Papa told me. He said, “Listen, son.” He said, “Find out what your thing is. Don’t try to keep up with the new generation. Don’t try to play the old generation. Play your thing.” Play your own thing. Don’t try to play somebody because you tried to play somebody else’s stuff, you try to Philly Joe or Max, you’re not Philly Joe, you’re not Max, you’re not Blakey, you’re not Tony Williams. You’re not Philly Joe. Play your thing. But first you got to do what? You got to find your thing. My pops always said practice makes perfect. That’s the way Trane said, “Man, I play so hard till my legs hurt. I have to sit and lay in the bed. I play in the closet. I played with my horn in the corner of the wall.”

Trane feared that his so-called cosmic music was going to start a lot of people going out, buying instruments and thinking that they could play with no training, no dues just by playing sounds and rhythms. There was a cat in Cleveland, from Birmingham, Alabama. Baddest man in Cleveland for 30, 40 years named Big Joe Alexander. Played with him in Birmingham at 15, that wouldn’t even allow Albert Ayler to come on the stage because he said Albert could not play. Albert didn’t really get any recognition until he went to Europe. A lot of cats did that and they became famous in Europe, and then they came back to this country and people accepted them. Mutawaf, last night he was talking about this Jamaican or West Indian that was in Sweden when he went over there. He said, “If you Black,” said, “They so crazy about jazz and they really don’t know it. All you got to do is get you an instrument and some drumsticks and walk around like you can play and you can’t even play. They don’t know it, and they’d be worshiping you.”

It’s changed a little bit now. I’m talking back in the ‘60s. That’s 50+ years ago. There’s a lot more of the music happening overseas, especially Japan. That’s where we expect the biggest sales to be. Do you know a copy of Al-Fatihah just sold in a bid process on eBay of one of the original Black Unity albums for $6,400? People going around and talking about this music, like it’s the holy grail. Like I tell I’m sitting up here and after we heard that stuff, after we did it in the studio and they played it back, I said, “Is that me?” Come on, you jiving. I must be in a trance. I played that?” I used to be sitting up there watching my hands and feet. I was no longer playing the music, it was playing me. It opens up your innards and shows you all of the loopholes and all of the toxic stuff that you need to be work on to release it. It also seeks, in the being of other people that participate in it, that toxic loopholes that need to be cleaned, if you just listen. Just sit down, shut up and listen. That’s all we were trying to say. I don’t play to please. I’m not Willie Best. I’m not Amos ‘n’ Andy. I started at 12, that’s 64 years. Don’t you think I deserve some respect? I’ve given 64 years of my life just trying to understand it. Never had any idea that I would master it. Then I just relaxed and I allowed it to master me. I just put my seatbelt on. And when you hear it, you will see me just riding the wind, brother, walking on the water. I’m alive. I’m touching base with the spirit. That’s all the drums were used for in Africa. That’s what they were used for, to revive the spirit, to drive out the evilness, to call the spirit down.

Now, when you get this new album, at the end of, “In the Light of Blackness,” we had drawn the spirit down in recording studio and they were communicating with us, and the Creator is my witness. I didn’t receive no revelation. You hear the spirit talking. That’s what we were seeking to do. Commune with the spirit. The spirit drops the light down through us and we dispersed it to the people, for what? The betterment of the people. Without that, it doesn’t mean anything to me. I don’t want to be cute. I don’t want to be dressed with cigarette hanging out of my mouth with that white witch running up my arm with a glass of whiskey down on the floor. Winking at a girl sitting over there.

CB: What were the circumstances for recording Al-Fatihah?

HS: We practiced every day for a year before we cut that record. We did it in the basement of an old building. No windows. Cement room that must have once been the coal room, probably less than 9′ x 12′. Everything we played bounced off the walls. Yusuf Mumin and Abdul Wadud would start a phrase and by then we knew where it was going. I tried to keep the fierce momentum and power going, but there was more to it than that. I had my drums tuned in a descending pentatonic, African scale. I would look for a harmonious sound on my drums for the chromatic phrases that they were doing on their instruments. Now I met and got to hug John Coltrane once in my life. When he and his band played, the five of them sounded like 25. So for the trio, you could hear 9 people, its the number squared, if you are doing it right. If you just sat there and listened, you could hear nine people playing because you all were locked in. By the Creator, I bear witness, I can’t go no higher than that, by the Creator, I’m not that bad. I’m sitting up there looking at my feet and hands and I knew it was not me playing anymore because I wasn’t even thinking the patterns. When you get to the point where you submit, you are no longer playing the music, the music is playing you, brother. Abdul and I used to do things things in the music, between us. You hear it on “Al-Nisa” (The Woman) with mallets. A bass instrument is tuned in forth, but a cello is tuned in fifth. I’m playing pentatonic, I’m playing fives. So we could do things together and you couldn’t tell whether it was the mallets or the cello playing. It was just powerful.

CB: Did Yusuf Mumin do most or all of the composing?

HS: They already had tunes when I got there. I started participating in composing one tune that we never released, which was a beautiful thing. I was working with rim shots and mallets, which was titled West Pakistan. We never did record that. That was the major tune that I participated in.

CB: I’m curious about how you associated with some of the other musicians from Cleveland like pianist Bobby Few, Albert Ayler, Donald Ayler, Frank Wright, Charles Tyler, Norman Howard, and others. Did you know that Albert Ayler’s parents had come to Cleveland from Alabama?

HS: Where are they from?

CB: His father was born in Mobile, his mother was born in Birmingham.

HS: Are you serious?

CB: Yeah.

HS: You can’t play Birmingham short, can you son? Now you going to start me preaching now. So Albert’s being goes back to Alabama? You better get out of here. You have just made my day, brother. Now I have to go back and listen at some of his music. I’m serious. I’m talking about footprints. Listen at me now. We share footprints and that’s the beginning. I got to go back. Bobby Few is still in Europe still in Europe, he’s an excellent piano player. Charles Tyler, Norman Howard, the trumpet player that wrote Spirits, that claimed that Albert stole that from him and recorded it. Frank Wright, I’m just starting to hear so much about. I didn’t know too many of those cats. I had heard Bobby Few was there for about a year while I was there, and then he moved to New York. Frank Wright, I’ve never heard, recorded or live. Charles never heard. We didn’t cross paths because like I said, we were just getting ready. When Abdul Wadud went to Stony Brook, we decided to move to New York and the group broke up. Now here’s where the Creator enters the scene. We never made a dime off the first 500 records pressed, self-produced. We produced all of this by ourselves. That’s why it is so historic. 52 years later, here comes Pierre Crepon in Paris and Matt Early the producer in Cleveland, who were taken in by the music when they were teenagers and actually love us because of that.

Here comes this man and says, “Well, I want to do an interview about you all. I’m very interested in your music.” Mutawaf, the bass player, introduced them to us because he’s such an Albert Ayler fanatic. You’re talking about a fanatic. He has made a trip all the way from Paris to Cleveland to go visit his grave, and he knew of Mutawaf in some type of way. They found each other and in the conversation, Mutawaf started talking about playing with a group called the Black Unity Trio. Matt had been a fan since he was a teenager. Guess what happened? I’ll show you how the Creator is the greatest. Yusuf is in town over at Abdul Wadud’s house. They’re watching TV. Just at this time, the Creator says, flash this on TV. Here’s this record company that comes on with an advertisement. Do you want to record your album?

They sit up, they’re watching this. They say, “Let’s at least investigate it. We might want to try to do something and re-issue Al-Fatihah.” We didn’t have nothing but albums. We didn’t think we even had the masters. Ron gets on the phone and call his lawyer, who’s producing the album. He’s also the Assistant Marketing Director of this record company. The man dropped the phone. Ron told him who he was, he said, “I’ve been looking for y’all, for 10 or 15 years. I thought y’all was dead.” He said, “I just flew back from LA and listened to y’all album the entire three, four-hour flight.”

We were so far ahead 52 years ago, the music still sounds present today. It is not antiquated. It’s not aged. It’s still out there. Because nobody’s taken it, brother, any further than what you hear on Al-Fatihah. The other reason they want to buy it in Europe, Japan, and Asia, the ‘60s when black folks were in politically, styles of dress, hair, music, art, literature, dance, has become extremely popular all over again.

We cut it December the 24, 1968. We didn’t release it on the general market until 1970. It came in number one as the avant-garde privately released by one publication in Europe. Black market release, they call it, when you do it yourself with no major contract. I saw a tenor player, brother in Germany who was playing. He said, “If you want to play this music, this album with the Black Unity Trio, is the map to playing this music.” He says, “This is the holy grail.” Did we know this album was going to be this dynamic when we did it? Of course not. We felt what we had created, especially if we let it get out of hand was powerful enough to knock a plane out the sky.

I was only in Cleveland, maybe two and a half years. I only have experience with Countess Felder. She introduced me to play these gigs. Then when I cut in with Yusuf now I was strictly on the road because we didn’t play no gigs in Cleveland. Like I said, our music was not nightclub type music. We set up most of our gigs on the college concert circuit. We were hired to do a second album, but it was never released. I think it was entitled Mystic Vision, that was live at Western Reserve.

When we told the producer what we were trying to do, self-determination was our interest, not trying to sign a contract. We thought we could, but we really weren’t prepared. He gave us a complete directory of all of the black student societies at ever college in the East and the Midwest, because we were thinking about trying to go to the West coast. We in turn sent out about 125 of the 500 albums with a nice little introductory letter to these Black student societies, and from that we got work. I have documentation showing that in 1968-69, we were playing sets just like Trane. We were doing 45 minutes, nonstop sets going through different segments. Take a 30-minute break, come back and play another 45 minutes nonstop, going through different moods, tempos and patterns. You know what we were making back then per person? $500 a night.

CB: How many different colleges did you play? Do you remember where you had gigs?

HS: One might have been Wayne State and maybe University of Chicago, University of Toledo, of course, at Oberlin, where Abdul was a student. We played there two, three, four times a year, and in Cleveland at Western Reserve. As far south as we went was Miles College in Birmingham and Florida State in Tallahassee. We played at Atlanta at the first African People’s Congress. That was held on Clark College campus. Those are the ones that we did. We did maybe about seven or eight, because like I said, the group wasn’t together maybe a year and three quarters of a year. Like I said, they arrested me January the 13th when I was coming back from New York. They took me and kept me incarcerated. Took me back to Alabama that September. I had a conviction and federal probation for three years, I think it was.

I had specific guidelines where I could not leave the state, so I could not get back to Cleveland and New York to play. There wasn’t anybody in Birmingham playing no new cosmic music. I’ve got nothing against Duke Ellington, but they were still playing “A Train” and “Satin Doll.” I’ve played “A Train” and “Satin Doll,” a thousand times. I don’t want to play it no more. So I didn’t mix well. I’ve never been a good bebop drummer. They were still in primitive, not advanced bebop. They were still playing tunes like “Au Privave,” “Billie’s Bounce,” and “Cherokee.”

CB: After you came back to Alabama, what did you do?

HS: Zilch. One of the low points in my life, because absolutely nothing was happening. I was the oldest of the Muslims in the community in Birmingham, in fact I was the only Sunni Muslim there. I knew the most Quran and the most Hadith, so I became the Imam because I knew the duties. I didn’t feel that the Imam of the community should be playing in night clubs. We finally ran across a Hadith attributed to Umar, Radhiallah Anhum, where it says they went on a campaign once with some Sudanese African brothers and they were in camp. They were playing the drums and dancing. He went to Muhammad, Allāhu ʿalayhi wa-sallam and said, “You think they ought to stop all of that foolishness and jumping around?” He said, “No, leave them alone. That’s a part of that culture.” That’s when we started playing again. We had lost two, three, maybe five years.

CB: So you were in Birmingham all of the 1970s?

HS: Yeah, all of the ‘70s. I thought I’d tripped out there. It was really hard as an artist not to be able to present my artform. I was in Birmingham from ‘64 to January of ‘68 in the ‘60s. Then New York and a little bit, coming back and forth between New York, Pittsburgh, and Cleveland. Then I was there, the majority of the ‘70s and ‘80s. I care not to discuss.

CB: You do have some plans to record some other groups, right?

HS: I have been playing with saxophonist Hasan Abdur-Razzaq. We have some stuff that we are working on now, even though we met all the way back when I was there.